“It’s all imaginary anyway. That’s why it’s important. People only fight over imaginary things.” Mr Nancy (American Gods, by Neil Gaiman)

There’s a certain sense of absurdity in writing these posts. I can’t explain it yet, but I’m sure it’ll make sense as the process goes on. The premise is that each piece be an invitation to visit the Great Feast & that each be rooted in the world of practice. Don’t expect detailed, philosophical exposition of what are complex themes. You must head further into the Great Feast yourself and follow your curiosity for that.

This is the first practice item. Each of which is simultaneously complex and simple. Part of navigating them well involves managing this seeming duality and noticing how one or the other can be more prominent as we develop a relationship with it as a practice space; a practice space that is experiential, and rooted in quality thought, individual and social, current and historical. Remaining sensitive to how the prioritisation of one, or the refusal of the other, can be a practice of control and resistance is also worth reflecting on. And this serves as a nice take on an enduring feature of the practicing life: always take opposites as relational working pairs that should open to other possibilities. Take their formulations, friction, symbolic role, and absurdity, as part of the practice material that is not a problem to be solved, but rather a landscape to be explored. Please remember this whilst reading on for I am not in the role of truth teller or guru.

Finally, this piece is pretty long. It’s difficult to elaborate on a complex issue without saying quite a lot about it and even so I have been brief throughout on points that would warrant many more words. I have divided the text into sections and if you like the work here at the blog, you may find it easier to read it in stages. That said, the whole is more than the sum of its parts and reading it as such will likely prove more fruitful.

The choice is yours.

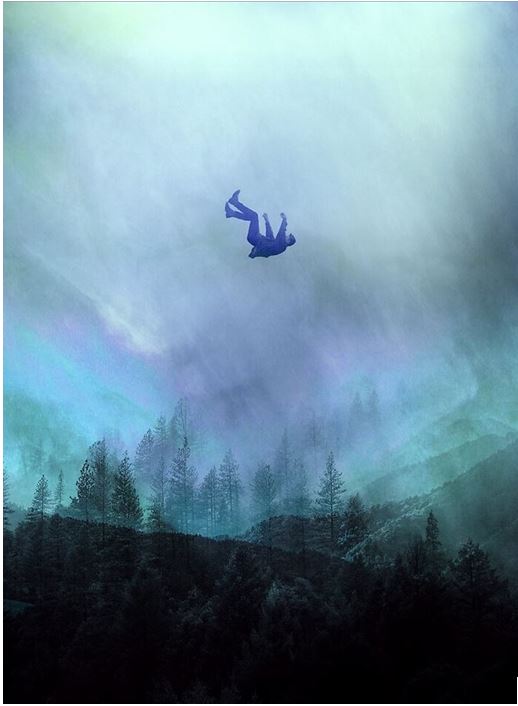

Item 01: No transcendence – banished to the earthly plane

“Have you thought about what it means to be a god? … It means you give up your mortal existence to become a meme: something that lives forever in people’s minds, like the tune of a nursery rhyme. It means that everyone gets to re-create you in their own minds. You barely have your own identity any more. Instead, you’re a thousand aspects of what people need you to be. And everyone wants something different from you. Nothing is fixed, nothing is stable.” Jesus (American Gods, by Neil Gaiman)

In the 2001 novel American Gods, British writer Neil Gaiman tells a story in which the world’s Gods have emigrated to the USA ever since its conception, on the whole been forgotten, and as a consequence find themselves struggling for survival, working as farm labourers, waitresses, prostitutes, taxi drivers and funeral directors; each hustling to get by. There’s a certain sobering image that emerges out of the story; magic is contained, hope and cynicism battle for the hearts and minds of gods old and new. The new gods include figures such as Technological Boy, Media, and other manifestations of our modern age.

Gaiman’s idea seems simple enough, turning our modern vices and social constructs into gods that hold power over us and that are fed by our very attention and worship, and when that attention is no longer given, eventually cease to exist. He crafts a tale from this premise that subverts and surprises repeatedly and throughout the central character Shadow is revealed as all too human despite his occasional dallies with otherworldly power. The text constantly shrugs off easy narrative dichotomies of good versus evil, instead shifting what appear as dichotomies into the complexities of lives that disobey the rules of black and white ideologies.

This is not a book review. Gaiman’s work merely serves a useful function for this piece. It is, in some ways, a work of Metamodernism. It discards outright cynicism, the rejection of magic, and unseen power for a playful, complex take on our odd relationship with objects of worship, where things are always many things and never one, and never two. It consistently slips out of predictable turns and thus acts as a nice way to broach the old chestnut that is transcendence from a position that isn’t for or against, but is many things and all at once. And by broach, I mean broach. This topic is immense and there is no hope of me doing justice to its complexity here.

This is a mere practice item, not the whole story.

A. Big picture

The impulse to transcend is multi-faceted, multi-layered and woven through the myths, stories and projects we humans are invested in. It is part of the collective infrastructure of meaning making for our species. It is ubiquitous, deep rooted, and stubborn. Explore the history of the West, and the Judeo-Christian desire for transcendence, yearning for reunion with some form of a totality, and escape from our all-too-human condition are everywhere, but desire for final transcendent release is not limited to the West’s hodgepodge history: transcendence runs across the globe through the myths and stories of the many that have come and gone and remain. All the same, you might say we have been a little more obsessed with it in the western world than most.

Transcendence is woven into the fabric of our institutions, cultural products, political structures and projects, and the dreams that fuel each. Even where the secular appears to dominate, a transcendent desire can often be found. Transcendence is ubiquitous to the point of being invisible to the untrained eye and like many potentially dysfunctional characteristics, the problem of the thing tends to lie in its hidden powers to shape and direct, rather than its actual existence in a complex world. As an unspoken component of our psyche, individual and collective, it shapes the contours of thought, feeling and action in ways that we are all too often oblivious to and in the practising life this silent consent is not permissible. Eventually, we ought to come to terms with the role it plays in our own practices, formal or otherwise, and ask ourselves what we might like to do with it, how we are going to understand its allure, seductive powers, and tendency to cultivate yearnings for escape from the very material that is our pathway through this life.

Transcendence has a long history that we are not alien to: The desire for God, union with the universe, merging with the nature as Goddess; these are just some of the explicitly religious manifestations of the transcendent. Each may influence and infect our practices and the desires we bring to meditation and any other practice you cultivate in your life. Enlightenment is one of the great transcendent desires within western Buddhism as we all well know and this term continues to capture the imagination. Transcendence is also woven into our desire to use meditation to fix our problems, to get beyond our suffering self, experience bliss as an alternative to the range of familiar emotions and feelings we inhabit, or make ourselves a better person. None of this is wrong of course. It’s perfectly human to use whatever means we can to relieve pain, anxiety, and strive to connect to pleasure, relief, and sanity. There is nothing inherently wrong in attempting to improve ourselves either. Transcendence is more than just this though. There is the collective aspect too, and its current role in a hyperreal world of stimulation, meaning manufacturing, and the inhabiting of collective fantasies rooted in ideological escapism. Highly idealised attempts to fix political problems rooted in utopian myths are also manifestations of transcendence. Sometimes they are exactly what we need to push through change and strive for a better world, sometimes they are the basis for dictatorship, the cult of personality, or warped desires that would destroy a world in order to save it. Too many seem to think they know the difference.

To confront our individual and collective dysfunctional ways of relating to transcendence is to come up against the role of desire in shaping the individual as a consumer of experiences and products that solicit formulations of short-term transcendence. They run from video games to alcohol, from porn to Marvel movies, from social media to shopping, from intellectual indulgence to enlightenment obsession, from body perfect to digital futurism to full-scale luxury Marxism and the solipsism of Libertarianism. Perhaps we cannot exist without a desire to transcend what is current, what is past, and the inevitabilities of decay, old age and death that keep looming on the horizon. Existence has a very dark side after all: One characterised by disappointment, delusion, loss, pain, boredom, doubt, and other tasty morsels of existential dread, day-to-day monotony, and encroaching threat of the destruction of the myths that keep us happy, and dumb. To desire to escape, ignore, or avoid all these is perfectly human, though as Buddhism has pointed out, these modes of being in this world cause suffering too, and ignorance to boot, and more often than not lead to an inability to face up the reality of our circumstances in ways that would be genuinely transformational.

B. Working Definition

What is transcendence? Like any rich topic, it has a long and varied history, and there are a variety of uses and ways of approaching and understanding it. At its most basic, to transcend is to go beyond. To leave behind. To evolve. To change forever; for good and with no going back. To transcend is to get somewhere away from here and no longer be part of, or experience, or see, or think about, smell, touch and deal with this. In its fancier concoctions it is that union with god, the soul leaving behind its sins, its physical burden, lust, confusion, sadness and separation. It is life after death in a heavenly realm. It is the Buddha body fully purified and in ever lasting peace. It is full, complete, total, forever enlightenment with a capital T. It is finality and ending.

Transcendence is also a fuck you to existing orders. It’s educating yourself to get out of poverty. It’s overcoming addiction and doing something about the big black hole at your centre. It’s dropping the burden of your dysfunctional family history. It’s creating societies where being different is less of an issue, and where limiting, stifling identities are softened. It is new genres of music, experimental film. It is the capacity to think anew, at the edge of what we currently know, come up with theories that explain where we have been, gone so wrong, and might consider going.

Immanence is typically posited as the opposite of transcendence. In this way, its meaning is concerned with what is material, mundane, temporal and here and now. In some ways it is conservative in nature. In theology, immanence posits the idea that the divine is actually here and not elsewhere, right in front of your eyes. A Buddhist equivalent is recognisable in Zen with the notion that we are already enlightened and there is no more to this ultimate goal than knowing how to breathe, take a step, and cook a meal.

Time and place are fundamental to both readings. As practice items, this is a stimulating area of practice. How do we internalise concepts of time? How do we relate to physical space and movement? Especially if the basis for the relationship is rooted in a muddled conception of immanent being or transcendent desire. Where do the immanent and the transcendent meet in our beliefs, ideals and practice goals? Where does one truly exist i.e. as the thing in itself? And is there such a division in reality and if so how do you recognise the boundaries between one or the other in your words and deeds?

When you sit to meditate, these two accompany your practice whether you recognise their presence or not. There is no escape from either. For this reason, to view them for a period as practice companions can be deeply insightful. The role of these two can play havoc with outcomes when their presence is unrecognised allowing for the maintenance of beliefs that are uncoupled from our material reality. This applies as much to immanent ideals as transcendent ones. Be here now as solipsism is well recognised and an obsession with the simple present is not only a linguistic cul-de-sac, it makes its proponents more often than not pretty useless members of society, however harmless they might be.

Transcendence stands out as the more problematic of the two for a variety of reasons though. They include the denial of our animal inheritance, the silly dichotomy of nature versus nurture, the general aloofness towards the earth and it rhythms. More recent examples range from escapist realism (the Earth is fucked, let’s go to Mars and leave the shitshow behind) to alternative lifestyle fetish (let’s all live like foragers, hunter-gatherers, in eco-communities, and leave Capitalism and city life to normies). Each is an attempt to escape from this to that, each is rooted in variations of denialism and a refusal to think seriously and in a sustained fashion alongside the complexity that marks the human condition and the better potential for elaborating practices rooted in the material reality of our circumstances. Our fantasies have consequences and when rooted in escapist desires to get away from the screams of a planet heating up and the many species suffering, it is hard to justify them.

Ideally, we would establish a far saner and explicit relationship with and between immanence and transcendence. An excess of transcendence would be curtailed by a realistic evaluation of the real-world, material conditions we are situated in on the largest scale possible. Theoretical, religious or spiritual projects would be rooted in a realistic evaluation of what is immanent to the individual and wider society and we would always start from there; rather than an idealised image of a world that does not and cannot exist.

This applies to the world of practice too. Rooting the aims and goals of practices and traditions in the here and now of the world outside the bubble of Buddhism or spirituality is the start off point. A meditation or Buddhist teacher may teach and then claim all kinds of things, but how do those teachings and claims match up to the world you exist in. What role does immanence play in claims concerning meditation? How realistic are they? Does the tradition or teacher invest a great deal in notions of enlightenment, nirvana, liberation, or big up pro-positive emotional states as ideals we are expected to one day inhabit most of the time? This is all merely scratching the surface of what can go on in dharma halls, mindfulness courses, and teachers teaching Buddhism and meditation. Mere claims of science, rationalism, or empirical commitments are unlikely to be all they claim to be due to the structure of desire that connects most of us to Buddhism, meditation and the spiritual more broadly in the first place.

C. Practice

This one is generally tough for most folks and I have not been an exception in finding the loss of certain ideals deeply challenging. Holding out for escape, an afterlife, or some other post-mortem fix is comforting. Just because you contemplate death and impermanence, doesn’t mean you have really come face to face with your mortality. Desiring big transcendent outcomes in this life is also an issue. Wanting to be happy as a baseline experience, desiring a forever calm mind, and eradicating all your weaknesses are all forms of dysfunctional desire that seeks to transcend the human condition of imperfection. Accepting limits, appreciating our specific range of imperfections, and working with the real material of self and circumstances is often a downer. Giving up holding out for fully realised selfhood can cause strong reactions.

Non-practice in many ways provides a reset button to the impulses of ideological compulsion and enactment. Confinement to the Earth and to our physical bodies is a start off point for non-practice and I would suggest that the Earth is the original reset point for us humans. An intimacy with immanence as confinement to this space is thus essential and considering it as specific confinement to the Earthly plane is a useful discipline. It doesn’t mean you can’t explore transcendence, put it to use, contemplate it deeply, but the payoffs are so costly that banishing it from your existence for a period can be a sobering, necessary step in weaning yourself off of the drug of escape. Go cold turkey for a period long-enough to trigger the sweats and other unpleasant withdraw symptoms and see how you handle a life without God, a next life, or some substitute for either. Facing up to the possibility we may never consistently be our best selves can be similarly traumatic. “Is this it?” you may find yourself asking. And for a period a good answer might just be “Yes, it is.”

D. Return everything to the world

The memes of spiritual transcendence can be returned to the earthly plane and understood as manifesting within its confines. Doing this can make them all rather interesting as statements on the human tendency to struggle with its condition. Try to not turn spiritual coping mechanisms into happy places to retreat to from the pain of existence and see them as human attempts rooted in the wonders of the human imagination to make sense of a world that is beyond our capacity to understand it in any way fully. One way of doing this is to deconstruct, no, not take apart, but trace origins of concepts that are part and parcel of the practice tradition you are part of. To return everything to the world is actually rather comforting in an odd sort of way. It all becomes far more human and sobering.

Coping mechanism is a pretty good definition for much of human activity. Just in case it’s not obvious, hedonism is a coping mechanism, ever-lasting compassion is a coping mechanism, love-is-everything© is a coping mechanism, reincarnation as preservation of you/your essence is a coping mechanism. The pain of this life is very real and accepting it rather than always trying to get better is one of the most sobering practices out there in this period of late Capitalism.

Just for fun, contemplate how the desire for transcendence fuels human creativity at its best and worst. Look through history at the way this desire has fuelled the creation of so much that is great and terrible, and keep looking, and contemplating for longer than you might usually.

Try contemplating death as extinction, ceasing, annihilation. That should scare you more than a Freddie Kruger movie. Sit in that space for a while and watch how you yearn for a substitute. If you can resist, then relax, and then embrace this life as the totality of your existence. Liberation awaits ye who make it through, but it’s an odd sort.

I know that was harsh. I can be soft and nice too. You can start off more slowly and avoid this if it triggers an excess of angst. Here’s a simple meditation practice:

Breathe in the world, breathe out the world.

In doing so, intentionally exchange escape and higher states for embodied embrace of your existence with no tomorrow; then smile, and breath, and relax. You can also try returning whatever aspect of the world you breathe in exactly to its place. Return each object, image and idea to the material plane without adding embellishments. Do so with kindness if it suits you. Do so with determination if the attachment is strong.

E. A few additional practice questions

I teach and coach people and originally trained as a psychotherapist so for me it is natural to pose questions as a means to elicit engagement. I have been championing a far broader approach to contemplation. One that opens up the idea of questions and concepts beyond the typical conceptual meditation objects found in Buddhism. This remains a contemplative practice. I am not merely proposing reflection, rather good questions are introduced at the beginning or end of a meditation session, ideally when the mind is calmer, you feel grounded and present and the question becomes an embodied experience and not an abstract thought.

Ideally, good questions are posed at just the right moment and make sense for where you are at. A well-timed question can open up the world in incredible ways, destabilise convictions, and trigger profound insight or new understanding. Random questions are unlikely to do this and the wording will never work for everyone. Nevertheless, I have put together a few questions below that come out of the process of writing the above. You may find them interesting to play with. You may want to formulate your own.

- Can I allow the world to exist truly independently of my desires for it to be X? Not be Y?

- Can I see the world apart from my usual filters of meaning-making for a moment, at least?

- How can I stop suffocating life through my heavy handed lens of the moment?

- If a personal transcendent ideal is escapist and what’s claimed is not true, what then?

- What does it mean to be present to the now with that in mind?

- How does the desire for something other than just this (moment, body, space, etc) fuel the overlay of meaning onto life?

- Rather than superimpose a utopian or dystopian fantasy onto the world and build out from within its imaginary apparatus, can I build a vision or experience of this world from what is accessible to me?

Thanks Matthew.

I am still struggling to see what non-practice looks compared with practice, and how what you write above is influenced by non-philosophy. Here is my own answer to that question.

You mention non-practice above, and to start with the body and world, but this seems quite de rigueur for many practices. For example, zen practice is very much about being “embodied” and connecting through the earth via the zazen posture. And your practice questions above wouldn’t be out of place in some buddhist books. I am reminded somewhat of Joko Beck, which I guess makes sense given that chungpa rinpoche lineage which must inform your own practice history.

So there can be a tendency for practices that seek to escape transcendence through immanence to then end up transcendising immanence, for example, in Zen.

What I think you are bringing to the table is an alertness to this process that might be lacking for those that are thoroughly x-buddhised, such that these temptations can be recognised and resisted (i.e. non-buddhism).

I can see why then you refer to this piece as meta-modern, because it has that (post) “traditional” sense of buddhism (by traditional, I really mean non-traditional chungpa rinpochesque westernified psychologised **modern** buddhism) but with the “meta” awareness that non-philosophy/non-buddhism brings that creates the necessary distance (not too close, not too far) from practice.

And what you end up with is a practice that though deeply informed by buddhism is no longer buddhism, in that is stepped out of the trap of buddhism and isn’t seeking some transcendental goal, but is instead a balancing act of questioning but still engaging and navigating through a complex messy capitalist world with eyes wide open.

LikeLike

That’s a pretty good summary.

The project rotates around the theme of avoiding turning the world into a Buddhified vision so it should sheen close to Buddhism yet remain aloof to its sufficiency traps. The whole thing is really rather silly though. On a good day, we shouldn’t need non-buddhism, but alas we are so propense to the allures of group think, ideology and final answers to forever complex problems, that we need to train ourselves out of the fog of certainty and become creative again.

There is the potential for smugness in the non-buddhism project if handled inelegantly though, and I would warn those approaching this odd little project to be wary.

LikeLike

[…] An audio read. Original text located here. […]

LikeLike

[…] Practice Item #01 – The Imperfect Buddha“It’s all imaginary anyway. That’s why it’s important. People only fight over imaginary things.” Mr Nancy (American Gods, by Neil Gaiman) There’s a certain sense of absurdity in writing these posts. I can’t explain it yet, but I’m sure it’ll make sense as the process goes on. The premise is that each piece be an…imperfectbuddha.com […]

LikeLike

You may enjoy Charles Taylor’s Sources of the Self, Matthew.

What you seem to be pointing to has a rich yet undernourished genealogy in Western thought, e.g., the Epicurean-Lucretian school, see also Montaigne & David Hume, among others, which is “content to remove the burden of impossible aspiration. The liberation is not to a marvelous remaking but more like a home-coming to a garden, a grateful acceptance of a limited space, with its own irregularities and imperfections, but within which something can flower. The moral inspiration comes not from the prospect of transformation but from the hard-won ability to cherish this circumscribed space.” Sources of the Self, pp. 345-47

Charles Taylor says that it is evocative of “the pagan sense that man is and must remain below the gods.”

This includes Hume-like (or Buddhist or Taoist for that matter) skepticism that “liberates us from the vain striving to an impossible self-grounded certainty.” Note #44

Significantly, Epicurus and David Hume both met their painful and mortal illnesses with apparent continued good cheer and equanimity.

I guess this reflects that a mind that drops it’s salvation projects realizes no salvation is needed after all – not even from death.

😊🙏

LikeLike

What a wonderful comment. Thank you for visiting. There’s so much in your few lines and I am afraid my response will be meandering.

I am a familiar with Taylor, but not the book you mention but shall certainly take a look at it. Thank you.

I like your choice of words, ‘an undernourished genealogy’ and am, as it happens, just finishing off a biography of Montaigne by Sarah Bakewell!

I am in two-minds about the general thrust of your suggestion. It points to a current struggle of mine not illustrated in the piece above, which is really as old as the podcast.

I took a turn to immanence as an aggressive attack on the transcendence and the seeking of some final ending as a sort of cure for the fantasies I had absorbed since my youth and was overflowing with. It was a longish and painful process but ultimately incredibly liberating and humbling. I am still culling residues of escapism as I go.

That said, I currently find myself returning to the question of aspiration, of striving, and of individual and collective projects that aim at some formulation of transcendence. Especially in light of Russia’s attack on the Ukraine and therefore Europe as a whole and the whole, flawed democratic ideal that feeds the West. We must defend certain transcendent ideals, such as human rights, equality, freedom of thought, yet come to them as enclosed beings, forever imperfect and driven by very old impulses. I guess I wonder what the best of democracy looks like without the underlying Judaeo-Christian myths and the absurd fallacy of forever growth that our economic models have been built on.

What motivates people if not a shared fantasy? Politics is rooted in this. A shared fantasy of Gaia as sacred and where we can locate meaning, commitment and shared rituals would be a far better shared vision than our current one, though I do wonder whether it could be compatible with Democracy and to what degree it could avoid the excesses of collective escape.

I wonder what individual and collective striving looks like when rooted in many enclosures too; life-span, geographical space, limited resources, personal energy levels, capacity, knowledge, historical baggage, and so on. Buddhism certainly provides tools and ways of practice that can help with a reconfiguration of our historical rootedness but I have long given up on the idea that it can help us escape it fully in any way.

John Gray has been so helpful for me in realising the limits of the progressive-liberal ideals I grew up in too and their current hyper-real moment seems like a sort of death dance of the naive ideals that have driven the West for at least the last hundred odd years. Yet, so much of what constitutes liberal and progressive is so much of what I desire to see more of – so the question of striving, vision, desire and transcendence lingers on.

I guess, on a personal level, I see a return to the world and a commitment to materiality as a starting point for a revaluation of what it means to strive for something more; individually, socially, spiritually, materially.

Montaigne is useful as image-maker in this sense for sure. Bakewell illustrates well how he was deeply involved in the politics of his day and sought to use his grounded wisdom to guide events to better outcomes. He was no solipsistic subject retreating into his private world.

As I feared, a rather random reply.

LikeLike

What you are pointing to is exactly what the book is about!

The values of universal justice, benevolence & individual liberty of thought/expression/action, the affirmation of the inherent value of ordinary life, remain our modern “goods” yet the “moral sources” of them derived from a higher order (providence) … theism or deism … but are no longer the agreed upon sources for moral authority for those goods, although those goods remain to be undeniable goods for Western moderns, for most of us at least in the Anglo-Americanized cultural sphere which includes Western Europe, Japan, Australia & allies like the Ukrainians.

According to Taylor, the challenge of western modernity has been continued valuation of the goods yet a rejection of the underlying moral sources of authority for those same goods … so according to Taylor, the authority has turned inward to moral authority being rooted in the subject, whether as a rational instrumental agent (18th c age of enlightenment) or an expressive creator (18/19th c romanticism). But this is an unchancy source for moral authority as we are seeing all around us today!

The extremes of both polarities are problematic, e.g., the radically utilitarian tech bros who think they can upload into the Matrix or go live on Mars or their own private islands, and on the other, the neo-Romantics // anti-intellectualism of the New Agers, therapy culture, nature mystics, and some American Buddhists. Most horrifying outcomes occur, according to Taylor, when the extremes of both polarities are combined, leading to Nazism & Marxist-Leninism. And is what is happening now perhaps in Russia’s imperialism vision.

In the meantime, according to Taylor, all we can do is cling to our goods, even without transcendent, agreed upon or even articulated moral authorities against authoritarianism, and strive to avoid the extremes on both ends.

Well, at least until the next philosophical revolution arrives (akin to the axial age —- Confucius, Lao-Tzu; Upanishads & Buddha; Greek pre-Socratics) … imo, we are similarly in a liminal period … a transition between ages … and are experiencing all the chaos inherent to that.

However, Taylor (as does John Gray who seems more like a curmudgeonly Taoist than Western rationalist in some parts of the Silence of Animals), points to a third way … the epiphany… of Rilke, in which the essential goodness of life is affirmed, either spontaneously through “grace”, contact with Nature, or as an conscious existential choice (Kierkegaard; Dostoevsky; Nietzsche) … but that too may be a false polarity.

According to Taylor’s understanding of epiphany in romanticism or existentialism, the leap of faith or choice to affirm the goodness of being reveals the Goodness (divine order; providence) as Beauty, or the sacred vision, as the Transcendent/Infinite dimension of the Particular/finite, somehow includes the subject but is far beyond the subject. (Sort of like Spinoza’s god of infinite attributes, but us as humans can only participate in two – thought and extension- so fully non-dual, as our being is being-in-god, yet not identical, not gods of infinite attributes but creatures bound by our limited participation in only two of them, for example.)

That is a fantastic chapter of the book by the way …. Re: Kierkegaard, he points to a transfiguration in which “none of the details of one’s life changes” but “in choosing myself, I become what I really am, a self with an infinite dimension.”

And going back to your original post …. embracing the particularities of the finite unreservedly, the affirming choice of the ordinary as “the good” seems for many a powerful doorway into a transcendent or sacred view of the good being “divinely” so to speak affirmed as the moral authority for the good.

The problem we have as Westerners is that we have no clear system of meaning/philosophy to approach or receive such epiphanies, make sense of them in a way that is culturally relevant, and/or develop it as a source of moral authority for our values of benevolence, justice and liberty.

I think this is because the Roman Catholic Church for 1000 years ruthlessly executed any dissenters destroyed, banned or otherwise suppressed texts of the Western non-theistic non-dual Greek & Roman traditions. They certainly burned many mystics as heretics.

The Protestants didn’t turn out to be much better. Poor Spinoza and Hume had their books banned and burned in Protestant countries. Spinoza only published the ethics after his death, likely to avoid being murdered like one of his dear friends by a mob of religious zealots.

Then, with the counter swing to scienticism-rationalism, 20th century philosophy departments were take over by analytical positivism & psych departments for 80 years were in the complete control of behavioralist —- no one who cared about the mind, emotions, or moral or spiritual questions could get tenure or do even do research until the late 1980/90s.

So I think that the first step is to reclaim our own intellectual heritage so as to reground our Western values more securely by incorporating the non-theist, non-dualistic, non-transcendent (in the sense of an afterlife or rebirth) but uniquely Western sources of moral authority for our values. It’s there, just pushed aside in different ways and times.

We are not stuck with only the two subjective polarities— there is a third tradition, influential but often unattributed (Epicurus & Spinoza in particular).

.

Yes, we can and should draw upon the Chinese philosophical traditions as well as the great non-dual philosophers of India and Tibet to help us understand our own intellectual heritage, as well as articulate an alternative sources of transcendent impersonal and mutually agreed upon moral authority in more precise or universal terms.

In sum, I think you would love the book. Next on my list is David McMahan’s the making of Buddhist modernism. He was deeply influenced by Charles Taylor’s Sources of the Self.

Be well & enjoy the reading feast to come!

LikeLike

One final P.S., I think we need to reclaim our own intellectual & spiritual heritage as Western moderns, and not just try to import Buddhism or Daoism as source of moral authority for western values as nowhere did Hindu, Buddhist or Daoist structures of meaning yield what we would identify as Western values.

So how can they possibly be or serve as moral authorities for values they themselves did not produce? Tibetan Buddhism, for example, yielded a theocracy and what seem to be medieval social and political structures. Likewise, in other cultures, while not theocracies, they certainly weren’t democracies with rule of law & liberty, equality & civic participation as a core values.

Thus Americans can have an epiphany experience, turn to yoga or Buddhism or Daoism, to make sense of it yet with no guarantee of remaining true to Western values. Indeed, in my yoga community, I heard people express ideas that the whole Western modern political system is so corrupt & it would be better if it all burned down. What?!? Of course, that could be radical romanticism & not actually Hinduism … but the point is that I doubt that our Western values can realistically look to moral authority in non-Western sources.

This the dilemma we face & why perhaps as you mentioned, you no longer believe Buddhism will the solution —- how can it be given it did not yield Western political values, organically, from its metaphysics or epistemology, in those cultures in which it was birthed and nurtured? The similarities have been ex post reconstructions or reinterpretations via Western neo-classism or neo-romanticism on both sides, according to scholars.

LikeLike